Prof. Joel Hayward’s website archive

Joel Hayward, ZDaF, BA, MA Hons, PhD, FRSA, FRHistS

The Evening Standard article

MANAWATU

EVENING STANDARD

MIDWEEK-MAGAZINE

Wednesday, September 3, 2003, p. 16

The issue here is the freedom our forebears fought and died to give us, former Massey University Senior Lecturer Joel Hayward says of the controversy over his masters thesis on the Holocaust. It was a controversy that led to his investigation by a working party, his loss of employment as an academic and the destruction of an entire issue of History Now.

In Robert Louis Stevenson's classic tale Treasure Island, Blind Pew passed a simple black spot into the hand of Billy Bones, who rasped several final breaths of terror and then died. In April 2000 I received my own black spot, not from the hand of a hateful pirate, but from a respected university Vice Chancellor, Professor Daryl LeGrew.

His announcement that Canterbury University would conduct an investigation — by something to be named the Joel Hayward Working Party — told me in no uncertain terms and with just as much horror that death was imminent; not my physical death, of course, but my professional academic death.

I'm not mistaken or being melodramatic. Last year, after two years of suffering abuse, threats, suspicion, accusations, broken contracts and more threats, "I crashed and burned," to use a Kiwi phrase. I'm now an unemployed scholar with six books to my name and few [academic] career prospects.

I've said little until recently. It hurt too much, and it also seemed futile for an alleged "denier" to be denying his denial. I also believed that no-one showed much interest in the big issues that lay behind this story. Those issues are not about me and whether I was ever a "revisionist" or not.

Only a few individuals with their own agendas still try to convince us otherwise. This was all about a ratbag — these few claim — who, either because he was duped by others or because he believed so himself, once tried to rewrite "the truth" in his thesis.

Actually, the issue here is the freedom our forebears fought and died to give us. In a free and enlightened society no historical actions or events, and no area or type of historical inquiry, should be treated as so sacrosanct that asking questions about them, or arriving at unorthodox or even unpopular answers, constitutes a heresy. Historical events are not unquestionable religious dogma.

Canterbury University therefore should never have succumbed to external pressures from any minority or special interest group, however sincere, concerned and impassioned that group was. It should never have launched an external investigation into the "truth standards" contained within a masters thesis (the phrase is from the complainants), however unpopular or controversial the thesis's arguments were.

Many other options for the university existed — including mediation — which did not involve putting one of its former students effectively on trial and did not jeopardize the University’s obligations under both its Charter and the Education Act (1989). These documents emphatically state (to quote the Act) that students and academics "have the freedom, within the law, to query and test received wisdom, to advance new ideas and to state unpopular or controversial opinions."

Canterbury University was apparently scared stiff when the New Zealand Jewish Council's (NZJC) complaint came, as I was. The NZJC had every right to complain, of course, but the University did not have to respond in the manner it immediately chose. Yet, rather than stand firm and hold up the principles of free inquiry and free speech upon its huge institutional shoulders, it buckled and dropped them — on my examiners and on me in particular. I collapsed under the strain, and have now spent three years feeling crushed.

Canterbury Vice Chancellor Daryl LeGrew issued a public statement on 20 April 2000 indicating that "the university is dismayed at the level of upset to the Jewish community and regrets this deeply." That was a fine sentiment. I had expressed my own regret.

But Professor LeGrew added these revealing words: "We wish to work with the Jewish community to resolve these matters." No mention was made of "working with" the History Department, of "working with" the supervisor, or "with" me, the thesis writer, to resolve the matter.

Was the Vice Chancellor making a pre-determination of my guilt? His statement from later in 2000 (20 December, to be precise) makes me believe that this was the case: "From the moment the matter was first drawn to my attention earlier this year I was most concerned and my personal view then was that an apology was required. But as Vice-Chancellor I first had to wait for the independent review process to be carried out."

Moreover, the fact that Canterbury University under that Vice Chancellor's stewardship called the investigative team "The Joel Hayward Working Party," and not, for instance, the History Thesis Working Party, indicates the University’s desire to make me, the individual thesis writer, and not the wider issues of academic freedom, the bone of contention.

During my first grilling by the Working Party that carried my name I quickly reached the inescapable perception that, despite its head being a retired High Court judge, it was indeed little more than a medieval heresy trial dressed up as an objective investigation. I have never deviated from that opinion.

I would rather have been tried for a crime in a court of law, because at least in a court numerous procedures, precedents and laws would have bestowed on me every right and opportunity to defend myself fully. At Canterbury University I was not so fortunate.

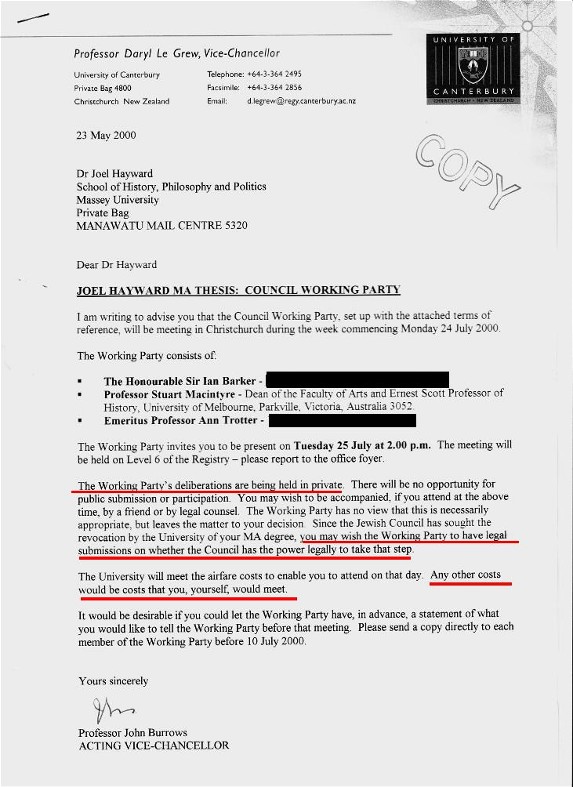

During the Working Party investigation I was invited to provide a legal submission as to whether the university had the right to strip my awarded degree from me. I was also invited to have legal representation whenever I appeared before the Working Party. All legal costs were to be borne by me, however, with no provision for what any accused criminal can access in our courts: free and expert legal representation provided by the state for those of inadequate means to make an adequate defence.

[This document — my first "invitation" to appear before the Working Party — is not in the original Evening Standard article. I have added red highlighting for emphasis. To comply with privacy legislation I have also blocked out personal addresses.]

I did pay a lawyer to investigate Canterbury's ability to strip my degree. He concluded, soundly, that unless dishonesty could be proven, my degree could not be revoked or even downgraded. It took me a year to pay off that lawyer for his small service, and I was not able to afford any other legal representation during the following eight months of the Working Party's proceedings. I was then, as I am today, still paying off my student loan.

The Working Party would later criticise the [Canterbury] History Department for not having had a specialist to supervise my particular topic back in 1991. This was an ironic conclusion given that not one of the three members of the Working Party possessed specialist knowledge, or, as I quickly came to believe, even a sound working knowledge, of the subject area.

The complainants paid a significant amount to employ the services of Cambridge Professor Richard Evans, who had previously testified in a London trial initiated by David Irving, the world's leading revisionist. Evans submitted to the complainants, and thence to the Working Party, a 71-page report. In language that even the Working Party considered strident and over-the-top, Professor Evans insisted that my thesis was not motivated by racism or malice but was very seriously flawed.

I could not afford to employ an expert to counter Professor Evans's report, which was in any event severely criticised as "adversarial," "not objective" and "partisan" by Professor Gerald Orchard, one of New Zealand's most highly regarded lawyers.

For my part, unable to hire an expert historian, I did the best job I could myself. My principal defence was not on issues of fact or interpretation, although I did identify several errors in Professor Evans's own work and the other complainants' papers.

My key defence was that Professor Evans was judging my decade-old thesis by far too high a standard. I was, after all, only in my fourth year of tertiary study when I had written the thesis. I was not a doctoral student, much less an established scholar with a string of books to my name. Professor Evans was judging me by that very highest of standards, as even a member of the Working Party let slip on one occasion.

At no time was I permitted to cross-examine or question my accusers directly — which any court in the land would have permitted — and my written request for mediation with my accusers was denied. Moreover, I was kept in the dark not only about the testimony presented by my accusers, but also about the testimony of other Canterbury historians and general staff who were asked to appear.

The Working Party conducted all proceedings in private, without any public scrutiny, and without the presence of an independent observer, despite the fact that the purported reason for the establishment of that Working Party was "public accountability".

In my first appearance before the Working Party I was even castigated for being argumentative when I said I felt unable to sign previously unseen legal documents without being able to take them away to read carefully and reflect on.

The Working Party's Report, released in Christmas week 2000, was an unsatisfactory document. As Dr Thomas Fudge recently observed: "It appears to have been intended to soothe by offering a compromise solution." That is, it would give me a good thrashing by criticizing my research as badly flawed and my conclusions as perverse, which would hopefully mollify the complainants. But, because the thesis revealed no malice or dishonesty, it would not strip my degree from me, thus hopefully placating all academics and students deeply concerned at such a possibility.

No-one involved except for Canterbury University and its History Department (although the latter not unanimously) has embraced this compromise conclusion. And so the controversy has survived.

Moreover, for me, the accused, there was no appellant process. To whom could I apply in search of the natural justice I strongly believe I was denied?

Although I'm pleased the Working Party found my research to be honest and lacking any malice (dishonesty was legally the only grounds for revoking, downgrading or otherwise altering my degree), Canterbury University nonetheless made a sacrifice of me apparently to placate a third party complainant. By calling my thesis flawed, perverse and undeserving of its first-class honours, it downgraded the thesis in all but formality.

The report and surrounding publicity rendered my chances of rebuilding my academic career and regaining my good name very slim indeed. I felt broken but struggled on for another year or more as a Senior Lecturer at Massey University, my self-belief and psyche so battered that I found myself working with a Zombie-like emotional disconnection. My introversion grew and my decision-making abilities deteriorated. I was finished.

So, then, with a new Vice Chancellor and lots of lessons purportedly learned by the History Department, has Canterbury University regained its reputation as a haven for free-thinking on all topics? Does it now better uphold its Charter or the Education Act? I can only conclude: apparently not.

In May this year I learned for the first time that Dr Thomas Fudge, a highly respected Canterbury scholar, had written a journal article on the whole affair and the impact it has had on my life and career.

Within a[nother] day or two the journal itself, History Now, published by Canterbury's History Department, arrived in my letterbox.

By the time I read the journal, however, all other copies (over 500) had been seized on instructions of Professor Peter Hempenstall, the Head of the History Department, and would eventually be destroyed.

In June, after weeks of rumours, I emailed every member of the History Department virtually pleading with them not to destroy the issue. I made it clear that I wasn't defending the article — although I've subsequently stated that it was generally accurate — but was strongly opposed to its suppression on the basis that any such act would be seen as book-burning. Only two members of the History Department [Dr Chris Connolly and Associate Professor Ian Campbell] bothered to reply to my email.

The Department's outrage at Dr Fudge's article was primarily about the use of intra-departmental communications being cited in the footnotes. Some people objected to them altogether, and others said that they should have been cleared with the various authors first.

What didn't they want people to know? That some [members of the Department] had criticised my thesis without having read it? Or that others had read it and thought it quite good? The footnotes include both revelations.

Let me make one point clear: the most embarrassing footnotes related to me. They discussed my mental health and were from emails between me and Vincent Orange and used without my prior knowledge. Was I embarrassed? Yes. No-one likes their emotional heath discussed in public. Did Thomas Fudge do anything wrong? No.

Also citing violations of editorial procedure, even though none had existed previously, Professor Hempenstall and the History Department took what I consider a dreadful step. With the support of the Vice Chancellor, they chose to destroy the journal issue containing Dr Fudge's article and to replace it with a similar looking one that contained no reference to the original issue and nothing else of a controversial nature.

And it still hasn't ended. Associate Professor Ian Campbell had to resign as editor of the journal (even though the replacement issue still bore his name) and Dr Fudge has, in disgust at the greater importance placed on "collegiality" than on academic principles, indicated his intention to resign altogether from his Senior Lectureship.

Fudge's students are the victims here. They pay huge fees for world-class tuition. Yet Fudge, rated very highly as both a teacher and a ground-breaking scholar, will soon depart for a job who-knows-where.

Now I hear that Canterbury University authorities have asked all History staff not to communicate with the media on either the "Hayward Affair" or the "Fudge Affair," and have also instructed Dr Fudge not to discuss either affair with students. Although the University authorities are doubtless trying to put these controversies behind them, they are also shutting down debate and the healthy exchange of ideas. What must their students think?

If I can summarise any lesson from my awful experience, it is a pessimistic observation on the state of health of our universities. I now believe that many staff within the Humanities at New Zealand universities care little about freedom of enquiry and expression. Many hold too loosely, or not at all, to the time-honoured principles of freedom:

- that universities are the marketplaces of ideas;

- that universities are havens for free thought and inquiry;

- that students should engage even controversial issues;

- that students should test the boundaries of knowledge;

- that teachers and their parent institution should defend their students' rights if they make mistakes or unintentionally cause offence in the process.

Many lecturers, while stating the opposite, actually use their markers pens to encourage uniformity of ideas and to discourage free-thinking. This may sound like a harsh statement, but am I wrong? Ask the students.

— Dr Joel Hayward

Click HERE or on the navigation links on the left of the page

to read the famous suppressed HISTORY NOW article.

Dr Joel Hayward is a New Zealand scholar, writer and poet. Dr Joel Hayward is also a world recognised military historian. Although some people know Dr Joel Hayward’s name because of a masters thesis on Holocaust revisionism that he wrote at Canterbury University in Christchurch over a decade ago Dr Joel Hayward is not a Holocaust revisionist and does not support Holocaust revisionism. Dr Joel Hayward lives in Palmerston North in New Zealand.