Prof. Joel Hayward’s website archive

Joel Hayward, ZDaF, BA, MA Hons, PhD, FRSA, FRHistS

Thought Crimes?

Aspects of this controversy have not, of course, been only about my 1991 thesis. They have been about destroying me personally and professionally.

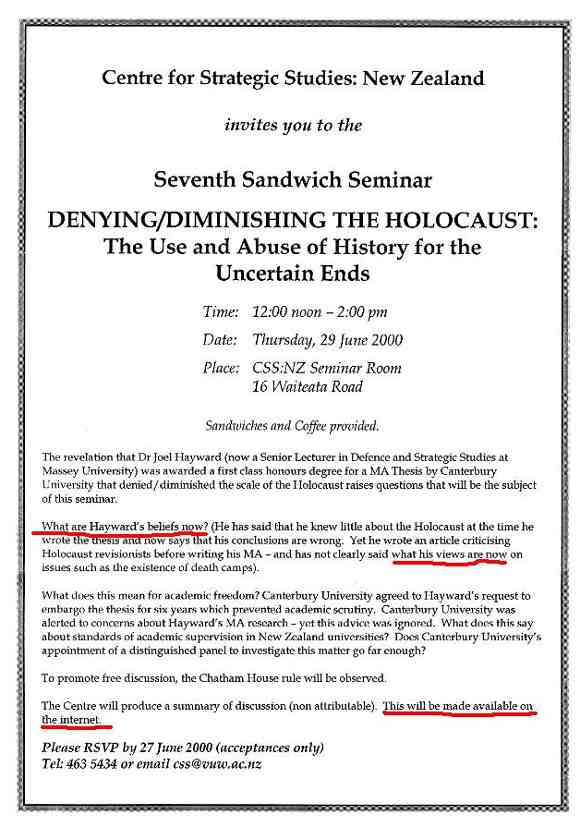

Lest anyone think I'm exaggerating or being melodramatic, let me point out that in 2000 an academic at another New Zealand university got the idea — I have proof of whom he got the idea from, but I'm not a vengeful person — that he would publicly "expose" me by holding a public seminar on my views.

The Centre for Strategic Studies: New Zealand (CSS:NZ) is a unit of the Victoria University of Wellington.

I was not invited to the seminar, and the organiser publicly stated that it would not be in my best interest to attend. Was this a threat of violence? I am still unsure. Readers can make up their own minds.

The Evening Standard of 2 June 2000 reported that "The Centre is promoting the seminar with a flyer questioning what Dr Hayward’s beliefs about the Holocaust are now, but hasn't invited him or even advised him of the seminar." The Organiser "said Dr Hayward was welcome to attend but it probably wouldn't be advisable." When questioned about the seminar’s total lack of relevance to his Centre’s mission statement, "Dr Dickens said he believed the subject did relate to defence and strategy."

But what was the focus of the seminar going to be? In what I consider a sadly Orwellian manner, my personal "beliefs," that is, my private "views" were going to be discussed, and the findings, in an unusual move for a seminar adhering to the Chatham House Rules, were going to be posted on the internet.

It still strikes me as outrageous that a person's supposed thoughts and beliefs — as opposed to his or her actions, public statements or publications — can be interrogated. Is merely having a supposedly contrary "view" or a "belief" now a crime in New Zealand?

If I were not present to share my views and beliefs how were my inner thoughts to be revealed to the attendees, and thence posted on the net? Perhaps the organiser had discovered powerful skills of telepathy that provided him with a clear understanding of my mind's workings.

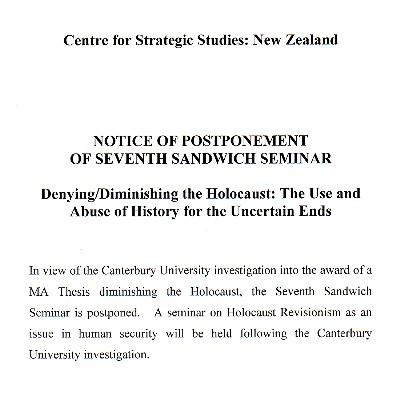

This seminar did not proceed. The topic was so roundly criticised as being outside the Centre for Strategic Studies' mandate that the organiser's motive were publicly questioned. As reported in the 3 June 2000 Evening Standard, even the New Zealand Army Chief of General Staff, Major General Maurice Dodson, condemned the planned seminar as "mischievous" and asked, "who would be speaking in Dr Hayward’s defence?" My own manager, Professor Ballard, also condemned the seminar and publicly challenged the organiser's motives.

In an apparent face-saving move, the organiser announced merely that the seminar would be postponed and that it would eventually be held (it never was!). Holocaust Revisionism — the organiser insisted, trying to demonstrate that his centre did have a mandate to discuss such an unrelated theme — was "an issue in human security".

Perhaps I can finally shed more light on the motives behind this seminar. The organiser and I were professional peers in the same field, defence studies, but I was proving more successful in terms of my perceived expertise and my publications record. This man was author of few papers and no books. But even behind this professional rivalry (never reciprocated by me) lay a more personal matter: the organiser had, in 1996, applied for the very job that I succeeded in getting, the lectureship in defence and strategic studies at Massey University.

Thus, public presentation of an individual's "thought crimes" was seriously planned as the topic of a university seminar in a liberal, parliamentary democracy. Were George Orwell to see this from the grave, he might well be sighing in a told-you-so way.

I do not consider it an overstatement that the organiser of this seminar was accusing me of "thought crimes." Clearly he believed my true thoughts were in some way actionable, and clearly he worried that Canterbury University’s "distinguished panel" was not adequate. Given that this panel, the so-called Joel Hayward Working Party, functioned in essence as a court, and was even presided over by a retired Judge of the High Court (and a QC), one can logically deduce that the organiser was suggesting that a better place for me to be investigated was a Court of Law.

Note: I only recently obtained copies of these Centre for Strategic Studies posters by seeking them under the Official Information Act. I thank the office of the current Vice Chancellor for providing them.

Interestingly, during 2000, the Acting Vice Chancellor at Victoria University of Wellington was Professor Roy Sharp. Professor Sharp then defended the Centre for Strategic Studies' plans to run the seminar on my "views," saying he would not interfere because this was a matter of academic freedom.

Yet this same Professor Roy Sharp is now Vice Chancellor of Canterbury University and is the man who approved the destruction of all copies of the May issue of History Now which had an article detailing my plight in recent years.

On 25 July 2000 (according to my telephone jotter) I rang and asked Professor Sharp why his views on "academic freedom" had changed so much over three years. In a tone of embarrassment he told me that he "couldn't remember all the details of the planned Victoria seminar" but claimed that he was "sure the circumstances of the two cases are very different in nature." He refused to be drawn further.